Artwork

Public artwork is often deployed to gently encourage passengers to move towards or linger in a space.

︎︎︎ Related entries:

Departure Hall

Duty Free Shopping

Floors

Maps

Signage

︎ Random Entry

Tags: airport design,

wayfinding, consumption,

sensory (visual, kinesthesia)

Departure Hall

Duty Free Shopping

Floors

Maps

Signage

︎ Random Entry

Tags: airport design,

wayfinding, consumption,

sensory (visual, kinesthesia)

Design Decisions

Airport planners deploy a range of strategies to guide passenger movement through the complex spatial sequence of airport terminals. Though no two airports are alike, the strategy at most airports can be distilled to one of just a few conceptual approaches, namely districts, connectors, streets and landmarks [1,2]. Regardless of the specific wayfinding strategy, a variety of devices can be used to guide passengers through space, including visual media like signage and maps, and architectural features like corridors and escalators. One of the most subtle interventions is the careful placement of public art.

In contrast to the direct, explicit communication of signage, artwork can gently encourage passengers to move towards or linger in a space. It can operate as a landmark at multiple scales - often serving as a distinct visual landmark in terminal interiors dominated by text, signs and pictograms, but also an indicator of the airport's geographic location [1,3]. In fact, while artwork often figures prominently in the design of a terminal, it rarely exists for the sake of the work alone.

“Untitled Lamp Bear”

by Urs Fischer, in Hamad International Airport in Doha, Qatar

“Untitled Lamp Bear”

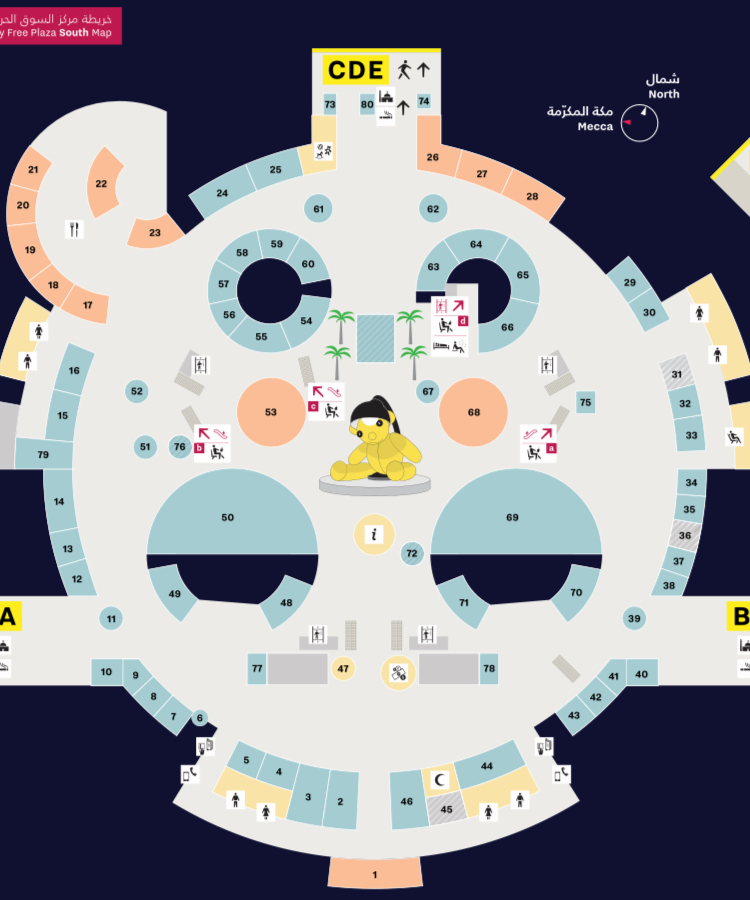

by Urs Fischer, in Hamad International Airport in Doha, Qatar  This bear is prominently displayed in wayfinding

maps throughout the airport

This bear is prominently displayed in wayfinding

maps throughout the airportIn Qatar’s Hamad International Airport, Urs Fischer’s 23-foot tall “Untitled Lamp Bear” (previously installed in front of the Seagram Building in New York City) marks the entrance to the airport's duty-free shopping area [4]. In Vancouver’s YVR, planners installed a number of artworks with region-specific themes as navigational aids [5].

In each case, the artworks, along with several others exhibited in each airport, figure prominently on wayfinding maps in the airport. Vancouver is notable because airport planners designed the interior of the terminal based on where the artworks would be placed [5].

Effects on Passengers

Beyond an aesthetically pleasing visual landmark, artwork can also subtly guide passenger consumption habits. Airport planners “often choose eye-catching artworks to entice passengers to move towards shops and restaurants. However, they also select artworks that convey themes which they believe will stimulate consumption. In many cases, these artworks refer to the region where the airport is located. These objects are suspected to lend to the terminal’s ‘sense of place,’ and airport authorities presume that this manufactured ambiance places passengers in the mood to spend” [5]. Though one study found that passengers exhibited a slight preference for terminal designs that did not reflect the distinctiveness of a particular location (in this case Holland, which was conveyed with “an artwork referring to a clog, big cows, and Delft blue tiles”), the artwork in question was not a context-specific work produced by a professional artist, as is typically the case in the real world [6].

Hubregtse’s research on airport art has identified kinaesthesia, or awareness of bodily movement, as a theme often found in various works [1,5]. This theme of free, unfettered corporeal motion stands in contrast to the carefully controlled, highly regimented sequence of processing activities that all passengers are required to complete. Peter Adey has argued that this symbolic representation of free movement is designed to operate on an affective level, soothing passengers and by extension encouraging commercial spending [7]. Recent examples include Singapore’s Jewel Changi Airport, which is organized around the Rain Vortex, the world's tallest indoor waterfall and New York’s La Guardia Airport Terminal B, which includes multiple movement-themed works such as Sarah Sze’s “Shorter Than the Day”, an ethereal, mobile globe and Jeppe Hein’s “All Your Wishes,” a collection of 70 steel balloons attached to the ceiling along a sinuous path through the terminals retail area [8,9].

Though its function can take many forms, the subject matter of airport artwork has its limits. Air travel can be a stressful experience for passengers, and airport stakeholders are keen to avoid upsetting passengers as they move through the terminal. For example, in 2004 Denver International Airport (DIA) removed portions of “The Luggage Project” from public view. The work, in which artist Max Yawney invited an international collection of artists to turn 43 suitcases into art, included three suitcases that were deemed “too stressful” for passengers because of the imagery they evoked, such as a handle made from a box cutter, and a suitcase splattered with blood-red paint [10]. Other artwork at DIA has prompted conspiracy theories about a “sinister influence” at the airport, particularly the mural “Children of the World Dream of Peace,” by Leo Tanguma [11].

“Planners... presume that these artworks, which lend to the terminal’s sense of place, will positively affect passengers’ moods and spur them to spend.”[1]

Singapore’s Jewel Changi Airport uses the Rain Vortex as both an artwork and as a spatial orientation strategy. (Photo: Safdie Architects)

Singapore’s Jewel Changi Airport uses the Rain Vortex as both an artwork and as a spatial orientation strategy. (Photo: Safdie Architects)

Sarah Sze’s Shorter Than The Day installation at LaGuardia Airport (Photo: Nicholas Knight)

Jeppe Hein’s “All Your Wishes” installation at LaGuardia Airport (Photo: Nicholas Knight)

- Hubregtse, Menno. 2016. “Passenger Movement and Air Terminal Design: Artworks, Wayfinding, Commerce, and Kinaesthesia.” Interiors 7 (2–3): 155–179.

-

Gibson, David. Wayfinding Handbook: Information Design for Public Places. Princeton Architectural Press, 2009.

-

Rowley, Jennifer, and Frances Slack. “The Retail Experience in Airport Departure Lounges: Reaching for Timelessness and Placelessness.” International Marketing Review, vol. 16, no. 4/5, 1999, pp. 363–376.

-

Tuchman, Phyllis. “City as Sculpture Park: In Doha, Public Art Program Reanimates the Tried and True.” 10 June 2019. ArtNews.

-

Hubregtse, Menno. Wayfinding, Consumption, and Air Terminal Design. 1st ed., Routledge, 2020.

-

van Oel, Clarine J., and F. W. (Derk) van den Berkhof. “Consumer Preferences in the Design of Airport Passenger Areas.” Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 36, Dec. 2013, pp. 280–90. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.08.005.

-

Adey, Peter. “Airports, Mobility and the Calculative Architecture of Affective Control.” Geoforum, vol. 39, no. 1, Jan. 2008, pp. 438–51.

-

Safdie Architects. “Jewel Changi Airport.” www.safdiearchitects.com. Accessed 17 June 2020.

-

Sheets, Hilarie. “Art That Might Make You Want to Go to La Guardia.” The New York Times. Accessed 17 June 2020.

-

“Artwork Removed from Denver Airport.” Airline Industry Information, Normans Media Ltd, 2004.

- “The Definitive Guide to Denver International Airport’s Biggest Conspiracy Theories.” The Denver Post, 31 Oct. 2016..