Duty Free

Shopping

“A passenger terminal has gone from being a little more than a bus stop to a two-hour check-in scenario...

Passengers need services while they are in a 'hold' situation and one way of paying for the increased security costs is to expand the earning of commercial revenue.”1

︎︎︎ Related entries:

Artwork

Floors

Departure Hall

Gate Lounge

︎ Random Entry

Tags: airport design, wayfinding,

consumption, psychology

Artwork

Floors

Departure Hall

Gate Lounge

︎ Random Entry

Tags: airport design, wayfinding,

consumption, psychology

Design Decisions

During the period of discretionary activity, or dwell time, a primary (revenue driven) goal for airports is “to direct all passenger flow past shops... integrate seating areas to encourage passengers to remain in commercial space... [and provide] adequate flight information screens to keep people informed in the trading areas" [1]. In other words, “airport authorities attempt to create spaces where passengers are more likely to spend money and time, and they do their utmost to hold them there” [2].

“Major international airports are nothing short of international shopping malls. London’s Heathrow Airport, for example, comprises of 66,000 sqm of retail space” [3].

One of the primary design goals of these spaces is to ensure that passenger stress levels remain low, to create a general sense of ease. Airport stakeholders know that “...the moment you feel comfortable, you’ll take some time to relax and you’ll buy some coffee or perfume” [4]. For instance, creating a close physical link to departure gates reduces passenger concerns about boarding their flight in time [5]. Subtle applications of artistic ceiling designs or flooring patterns can also contribute to keeping passengers in a retail environment longer [6]. Most airports (75%) use a single vendor for duty free sales, whereas for other types of retail nearly all (96%) prefer multiple entities [7].

Effects on Passengers

Consumers in a positive mood evaluate products more favorably than those in a neutral mood [8]. Retail products are also more appealing in a more pleasing space [9]. The unique range of emotions that travelers may experience at an airport, including anxiety, stress, and excitement, make them prone to act differently than typical shoppers in an ordinary retail situation [10].

One unique aspect of airport shopping is the anonymity provided by the airport. Socially undesirable shopping habits, such as impulsive purchases of goods, can be facilitated by a feeling of anonymity. As a result, nearly 70% of airport shopping is done on impulse - where shoppers have no prior intent to purchase a specific brand, or even category of item [11].

A 2011 study of 115 commercial airports found that, on average, a departing international passenger spent $26.80 on duty free shopping [7]. The most commonly cited reason for browsing in airport shops was “to fill in time” [12]. The reason for travel, duration of the trip, location of shops, knowledge of a particular airport, size of traveler group, and whether a passenger is flying on a low cost carrier have all been found to impact purchasing habits [3].

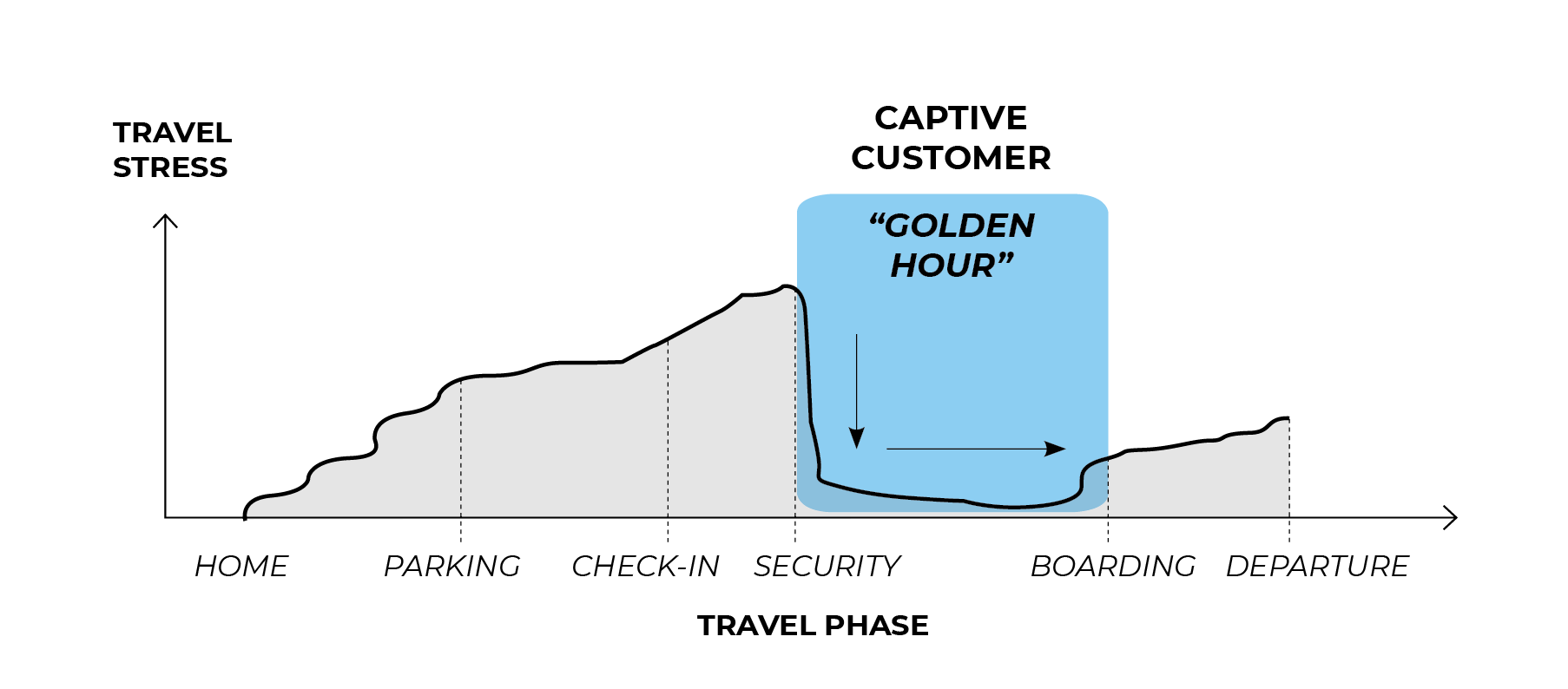

Passenger’s travel related anxiety through time. Highlighted region represents the time when they are most likely to participate in impulse buying [2].

- Thomas-Emberson, Steve. 2007. Airport Interiors: Design for Business. Chichester, England ; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Academy.

-

Adey, Peter. 2007. “‘May I Have Your Attention’: Airport Geographies of Spectatorship, Position, and (Im)Mobility.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 25 (3): 515–36.

-

Bohl, Patrick. 2016. “The Impact of Airport Retail Environment on Passenger Emotions and Behaviour.” PhD, Budapest: Corvinus University of Budapest.

-

Daniel, Diane. “Need to Get From Point A to Point B? This Guy Creates the Signs to Help.” The New York Times, 28 Sept. 2019. NYTimes.com.

-

Livingstone, Alison, Vesna Popovic, Ben Kraal, and Philip J Kirk. n.d. “Understanding the Airport Passenger Landside Retail Experience,” 19.

-

Hubregtse, Menno. 2016. “Passenger Movement and Air Terminal Design: Artworks, Wayfinding, Commerce, and Kinaesthesia.” Interiors 7 (2–3): 155–179.

-

Rimmer, J. (2011). “The Airport Commercial Revenues Study (ACRS) 2010/11.” The Moodie Report in cooperation with the S-A-P Group.

-

Isen, A. M., Nygren, T. E., & Ashby, F. G. (1988). “Influence of Positive Affect on the Subjective Utility of Gains and Losses - It Is Just Not Worth the Risk.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(5), 710-717.

-

Bitner, M. J. (1990). “Evaluating service encounters: the effects of physical surroundings and employee responses.” Journal of Marketing, 54, 69-82.

-

Lin, Yi-Hsin, and Ching-Fu Chen. “Passengers’ Shopping Motivations and Commercial Activities at Airports – The Moderating Effects of Time Pressure and Impulse Buying Tendency.” Tourism Management, vol. 36, June 2013, pp. 426–34.

-

Crawford, G., & Melewar, T. C. (2003). “The importance of impulse purchasing behaviour in the international airport environment.” Journal of Consumer Behaviour,3, 85-98.

-

Baron, S., & Wass, K. (1996). “Towards an understanding of airport shopping behaviour.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 6(3), 301-322.