Jetiquette

A new airport culture and a set of norms have developed from the implicit social contract between passengers and airports.

︎︎︎ Related entries:

Comfort

Illusion of Control

Jet Lag

Rituals

︎ Random Entry

Tags: social contract, proxemics,

psychology, sensory, culture

Comfort

Illusion of Control

Jet Lag

Rituals

︎ Random Entry

Tags: social contract, proxemics,

psychology, sensory, culture

Jetiquette operates hand-in-hand with the implicit social contract that governs the relationship between passengers and the airport. In exchange for security, efficiency, and access to flight technologies, passengers willingly limit one’s own autonomy and even enforce these policies around them by creating unspoken rules and etiquette. Rules and norms learned at one airport may generally be transferred and applied to another one [1]. It is the nature of airports as non-places that its rules and conventions are by and large uniform all over the world, independent of its true geographical context.

1) Jetiquette in service of efficiency:

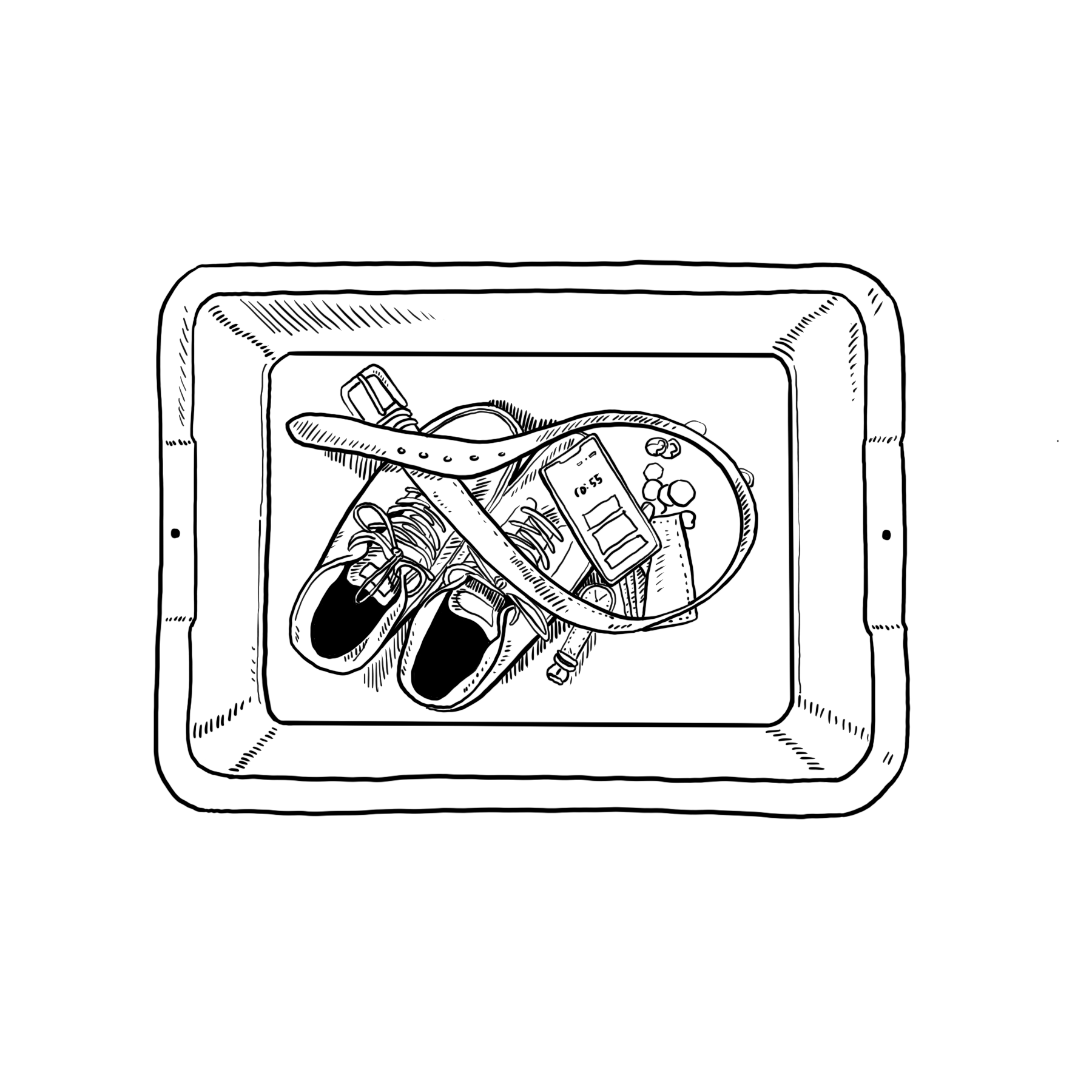

Knowing that voluntarily limiting one’s autonomy will facilitate a speedier experience, one does so willingly and encourages others to do the same. Such airport etiquette include being ready to produce identification papers at security checkpoints, or wearing simple shoes that do not require much time to take off. These may cause only a few seconds of delay, but perceived ignorance of these rules can cause outsize frustration among others [2]. Some even go so far to chastise others for creating interruptions in the orderly process, becoming more judgmental than they would be in other contexts.

2) Jetiquette in service of maintaining personal space:

On the plane, an extensive set of norms have emerged regarding one’s personal space. Personal space has been defined as "the emotionally tinged zone around the human body that people feel is their space" where individuals feel a sense of ownership and any intrusion of it leads to feelings of discomfort, stress, and avoidance [3, 4]. The variety of personal space encroachments that passengers undergo can include bodily noise, undesired conversations, undesired gaze, smells, physical contact, and physical proximity [4]. As a result, unofficial norms about whether to recline one’s seat, whether to use the armrest, or whether to make conversation have developed, albeit with many exceptions and mismatched expectations.

1) Jetiquette in service of efficiency:

Knowing that voluntarily limiting one’s autonomy will facilitate a speedier experience, one does so willingly and encourages others to do the same. Such airport etiquette include being ready to produce identification papers at security checkpoints, or wearing simple shoes that do not require much time to take off. These may cause only a few seconds of delay, but perceived ignorance of these rules can cause outsize frustration among others [2]. Some even go so far to chastise others for creating interruptions in the orderly process, becoming more judgmental than they would be in other contexts.

2) Jetiquette in service of maintaining personal space:

On the plane, an extensive set of norms have emerged regarding one’s personal space. Personal space has been defined as "the emotionally tinged zone around the human body that people feel is their space" where individuals feel a sense of ownership and any intrusion of it leads to feelings of discomfort, stress, and avoidance [3, 4]. The variety of personal space encroachments that passengers undergo can include bodily noise, undesired conversations, undesired gaze, smells, physical contact, and physical proximity [4]. As a result, unofficial norms about whether to recline one’s seat, whether to use the armrest, or whether to make conversation have developed, albeit with many exceptions and mismatched expectations.

These norms can be understood as strategies to help regulate the heightened anxiety and stress levels within ourselves and among each other. Many aspects of air travel trigger larger emotional and behavioral reactions than they would in other contexts. One explanation may be physiological; low cabin pressure contributes to dehydration and the reduction in the amount of oxygen carried in our blood, which can lead to fatigue, confusion, impaired decision-making, and the inability to self-regulate one’s emotions [5]. Additionally, there is evidence that constant exposure to loud noises causes an accumulation of cortisol, the stress hormone, in the blood [6], which contributes to one’s inability to control one’s mood, motivation, and fear. Thus the loud ambient volumes of aircraft cabin noise may also play a role.

“Research commissioned by Gatwick Airport in 2017 on the likelihood of passengers bursting into tears found that 15 percent of men said that they were more likely to cry while watching a film on a plane than if they saw the same movie at home or in a cinema. The figure for women was 6 percent” [7].

Another factor may be psychological inputs, such as anxiety about flying and loss of agency. According to psychologist Jodi DeLuca, the accumulation of the pressures to keep track of time and items, as well as the perceived loss of control and the fear of a possible crash can lead a person to break down emotionally once in the air. “We have little control over our environment while we are traveling by plane. Although we may not be consciously aware of our emotional vulnerability, our emotional brain is working overtime” [5]. This vulnerability may manifest itself in different ways, from people confessing secrets to strangers, or developing compulsive behaviors that do not occur in other contexts. As we find it more difficult to self-regulate our own emotions, relying on these norms might be one way one tries to impose order both on oneself and others.

![]()

- Eriksen, Thomas, and Runar Døving. 1992. “In Limbo: Notes on the Culture of Airports.” In The Consequences of Globalization for Anthropology. Prague, Copenhagen.

-

Marbles, Jenna. “What B*tches Wear at the Airport”. November 30, 2011.

-

Sommer, Robert. 2002. “Personal Space in a Digital Age.” In Handbook of Environmental Psychology, edited by Robert Bechtel and Arza Churchman, 647–60. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

-

Lewis, Laura, Harshada Patel, Mirabelle D’Cruz, and Sue Cobb. 2017. “What Makes a Space Invader? Passenger Perceptions of Personal Space Invasion in Aircraft Travel.” Ergonomics 60 (11): 1461–70.

-

Gajanan, Mahita. 2018. “This Is Why You’re Prone to Cry on an Airplane, According to a Psychologist.” TIME, June 12, 2018, sec. US Aviation.

-

Spreng, M. 2004. “Noise Induced Nocturnal Cortisol Secretion and Tolerable Overhead Flights.” Noise & Health 6 (22): 35–47.

-

Teitell, Beth. 2019. “Why We Turn into Different People When We Fly.” Boston Globe, July 9, 2019.