In-Flight

Screen

The screens onboard the plane allows passengers to look away: from each other, from the risk and uncertainty of air travel, and from their boredoms.

︎︎︎ Related entries:

Jet Lag

Rituals

Time

︎ Random Entry

Tags: technology, consumption,

sensory (visual, acoustic), waiting time

Jet Lag

Rituals

Time

︎ Random Entry

Tags: technology, consumption,

sensory (visual, acoustic), waiting time

Design Decisions

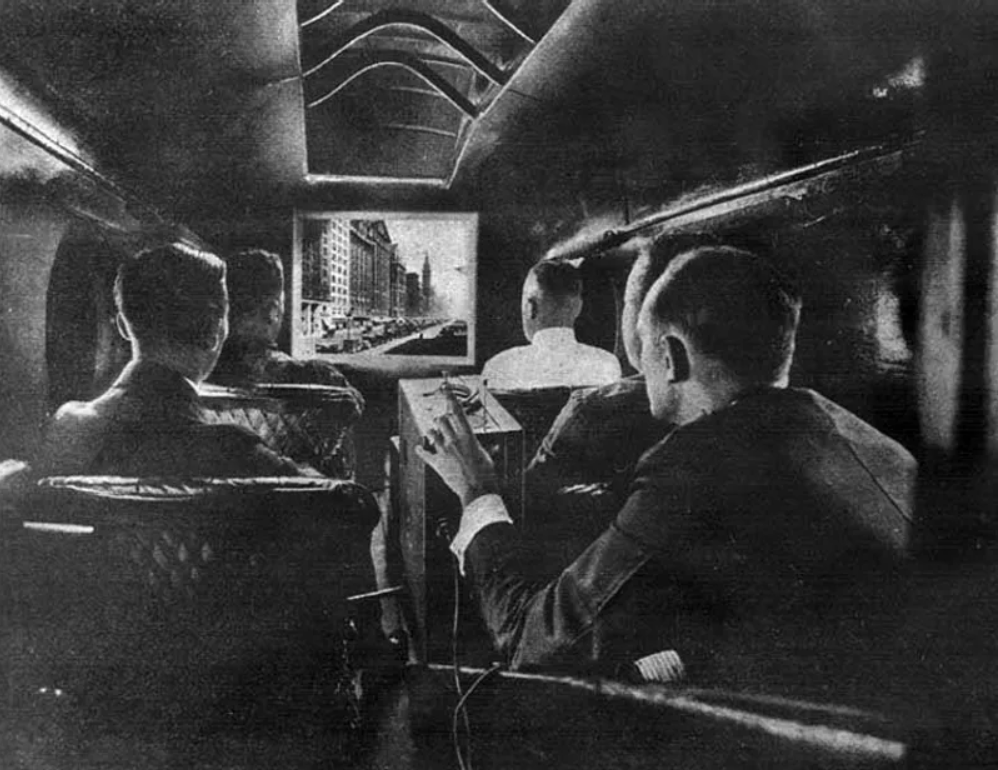

Beyond technologies associated with the provision of basic human needs, such as pressurization and oxygen, the aircraft cabin has been a site for the development and deployment of screen technologies nearly since the advent of commercial flight itself. In fact, the first documented instance of in-flight entertainment occurred only 7 years after the first commercial flight [2].

Earliest examples of in-flight entertainment [2]

Earliest examples of in-flight entertainment [2]Screens often function as a welcome distraction, encouraging passengers to distract themselves from the experience of flight. They are intermediaries, shielding passengers from the realities of flight and the banality of long distance travel by keeping passengers entertained, calm and content. Currently, we navigate nearly all forms of in-flight entertainment through screens – whether the exhibition of films and television shows, the playing of music or video games, or the display of data relevant to one’s particular flight. According to one recent survey, along with fresh food, in-flight screens have the greatest positive effect on customer satisfaction [3]. The value of in-flight entertainment has been a catalyst for developing increased connectivity in-flight.

Typical seatback in-flight entertainment

screen design

Typical seatback in-flight entertainment

screen designWe experience other types of screens in-flight as well. Windows in the main cabin screen passengers from inhospitable atmospheric conditions, and provide an oblique view of one’s immediate surroundings. Other screens such as curtains, in flight magazines and safety cards can define our personal space, and protect from intrusions by fellow passengers. Inflight entertainment, then, is the cultural condensation of these contradictory impulses to bring the faraway closer (in place) but still maintain distance (through space) [4].

The basic arrangement and mode of interaction with screens can have significant implications for a passengers experience. The delivery method of In-flight Entertainment has evolved from a limited number of shared overhead screens, to individualized seatback screens, to a Bring-your-own-device (BYOD) model predicated on the existence of the prevalence of personal electronic devices and increasingly robust networks of wireless connectivity and communication.

Effects on Passengers

General trends indicate that screens may be becoming less common [7]. Now that many passengers carry electronic devices, fewer airlines worldwide have seatback screens. The emergence of BYOD (Bring your own device) and development of novel wireless communications solutions means that the market for IFEC is predicted to grow to 10 billion dollars by 2024 from its current valuation of 5.1 billion (2018) [8]. Taking out screens does make some financial sense, as carriers no longer have to buy or maintain hardware, planes can be made lighter and thus more fuel efficient and seats can be made thinner, potentially providing for additional seating.

A unique aspect of the in-flight entertainment experience, as opposed to entertainment at a cinema or theater, is the option to opt out of viewing. Until very recently, airplanes were closed systems that were not connected to the outside world except through radio, and so could only show content that was physically stored on board. Beginning with the widespread adoption of inflight cinema in the 1960’s, airlines transmitted sound through headsets to avoid making every audience member a captive viewer of the chosen film. “This separation of sound from image runs counter to the ideal viewing situation in which the large image and synchronized sound overwhelm and envelop the spectator” [9]. This trend has continued with the increased personalization and miniaturization of the IFE experience, facilitated by the development of new technologies of wireless communication [10].

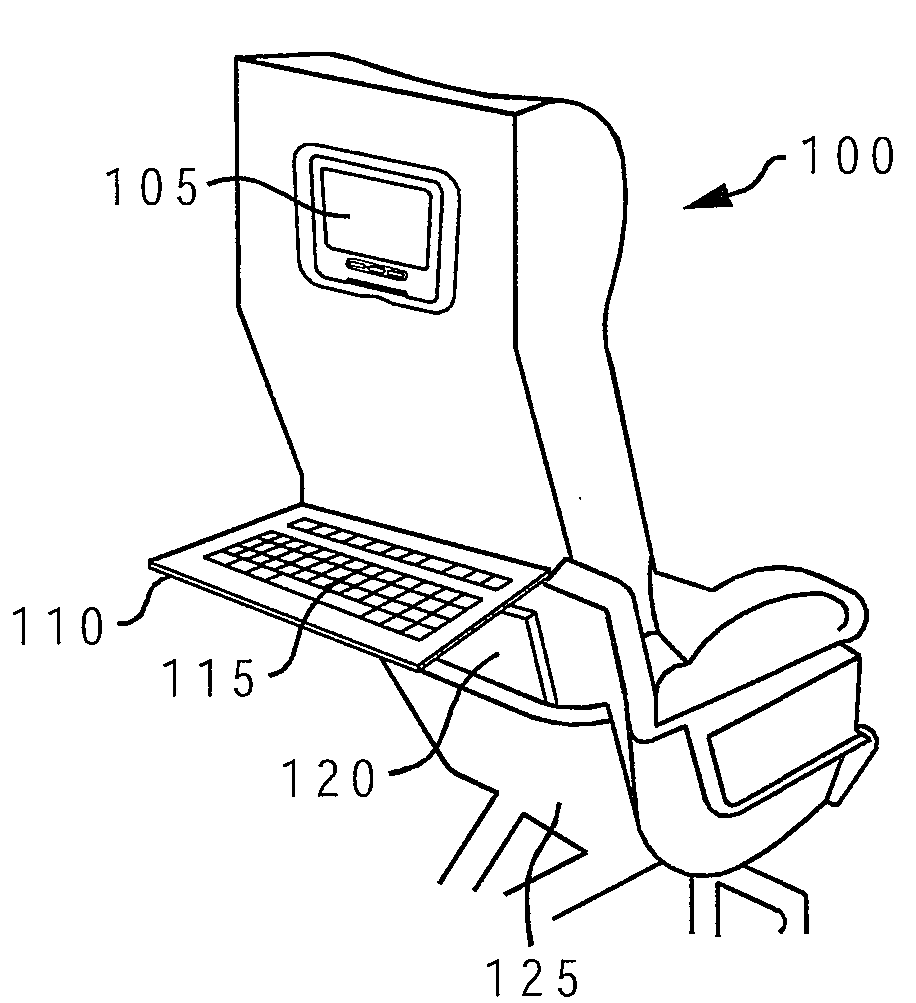

A design to connect laptops and keyboards to display on seatbacks [4] is a precedessor to more contemporary efforts to connect smaller

personal devices (e.g. iPads) to the seatback [5].

A design to connect laptops and keyboards to display on seatbacks [4] is a precedessor to more contemporary efforts to connect smaller

personal devices (e.g. iPads) to the seatback [5].

A recent survey of 7,900 aircraft indicates that entertainment is almost evenly split between the 3 methods (overhead, seatback, streaming) [5]. For every aircraft flying in the United States without IFE there are seven aircrafts that are [6].

What-Ifs

What if there were other forms of entertainment available in flight? Airlines provided more than just an electrical outlet and wifi?

What is there was a model of collective viewing and entertainment, similarly to watching a movie with friends?

What if in-flight entertainment didn’t require headphones?

- Groening, Stephen. 2013. “Aerial Screens.” History and Technology 29 (3): 295.

-

“Motion Pictures on the Screen While Flying through the Clouds at 90 Miles an Hour !” 1921. Aerial Age Weekly 13 (24): 584.

-

“2019 North America Airline Satisfaction Study” J.D. POWER. n.d. Accessed October 22, 2019.

-

Groening, Stephen. 2013. “Aerial Screens.” History and Technology 29 (3): 284.

-

Anonymous. 2018. “How Six Airlines Are Choosing to Keep Their Passengers Content and Connected.” Flight International, 2018.

- Mellon, James, and Murdo Morrison. 2018. “Who’s Switched On?” Flight International 193 (5629): 26–28.

- White, Martha C. 2018. “Those Seatback Screens on Planes Are Starting to Disappear.” The New York Times, January 1, 2018, sec. Business.

-

“In-Flight Entertainment & Connectivity Market | Industry Report, 2025.” n.d. Accessed October 22, 2019.

-

Groening, Stephen. 2016. “‘No One Likes to Be a Captive Audience’: Headphones and in-Flight Cinema.” Film History XXVIII (3): 114–38.

-

Lauer, Bryan Adrian. 2019. Wireless Cabin Seatback Screen Location Determination. US2019031366 (A1), issued January 31, 2019.