In-Flight

Food

Passengers’ perception of taste and smell change considerably in flight.

︎︎︎ Related entries:

Meal Tray

Meal Trolley

︎ Random Entry

Tags: systems design, sustainability,

sensory (taste, smell), consumption

Meal Tray

Meal Trolley

︎ Random Entry

Tags: systems design, sustainability,

sensory (taste, smell), consumption

Design Decisions

In the early days of commercial flight, in-flight food service consisted of cold items including ice cream, cheese, fruits, salad, and meats, and hot tea and coffee in thermos containers [1]. As airlines transitioned to larger kitchen galleys in the mid-1930s, regular hot meals became more and more common, with preparation on hot plates or pots with electrical heating coils [2]. By the 1950s, equipment in the galleys included several catering functions such as convection ovens, refrigerators, and service trolleys (See: Meal Trolleys). This enabled frozen meals to be kept in storage before being reheated in the ovens, greatly increasing the meal options available in flight [1].

“Meal times on long flights serve to distract the passengers. Especially on long trips, they are an important way of dividing up the flight into manageable lengths of time” [2].

History shows that the development of the meals and the galleys happened hand in hand; improvements in the meal service system greatly increased the variety and quality of the meal options available on the plane. Yet, despite all of the advances of the contemporary aircraft galley, the quality of airplane food is a frequent topic of derision today.

A significant contributing factor is the amount of time that must pass between food preparation, heating, and service. The meals, prepared on the ground, endure hours of storage and transport [3]. Once in the air, the meals are reheated and then distributed to hundreds of people. The sheer number of meals being delivered requires intricate logistical coordination at every stage, translating to a seemingly unavoidable amount of time passing before the food reaches every passenger. As a result, most airplane meals are doused in fluids and sauces in an effort to help keep the food from drying out or going cold [4].

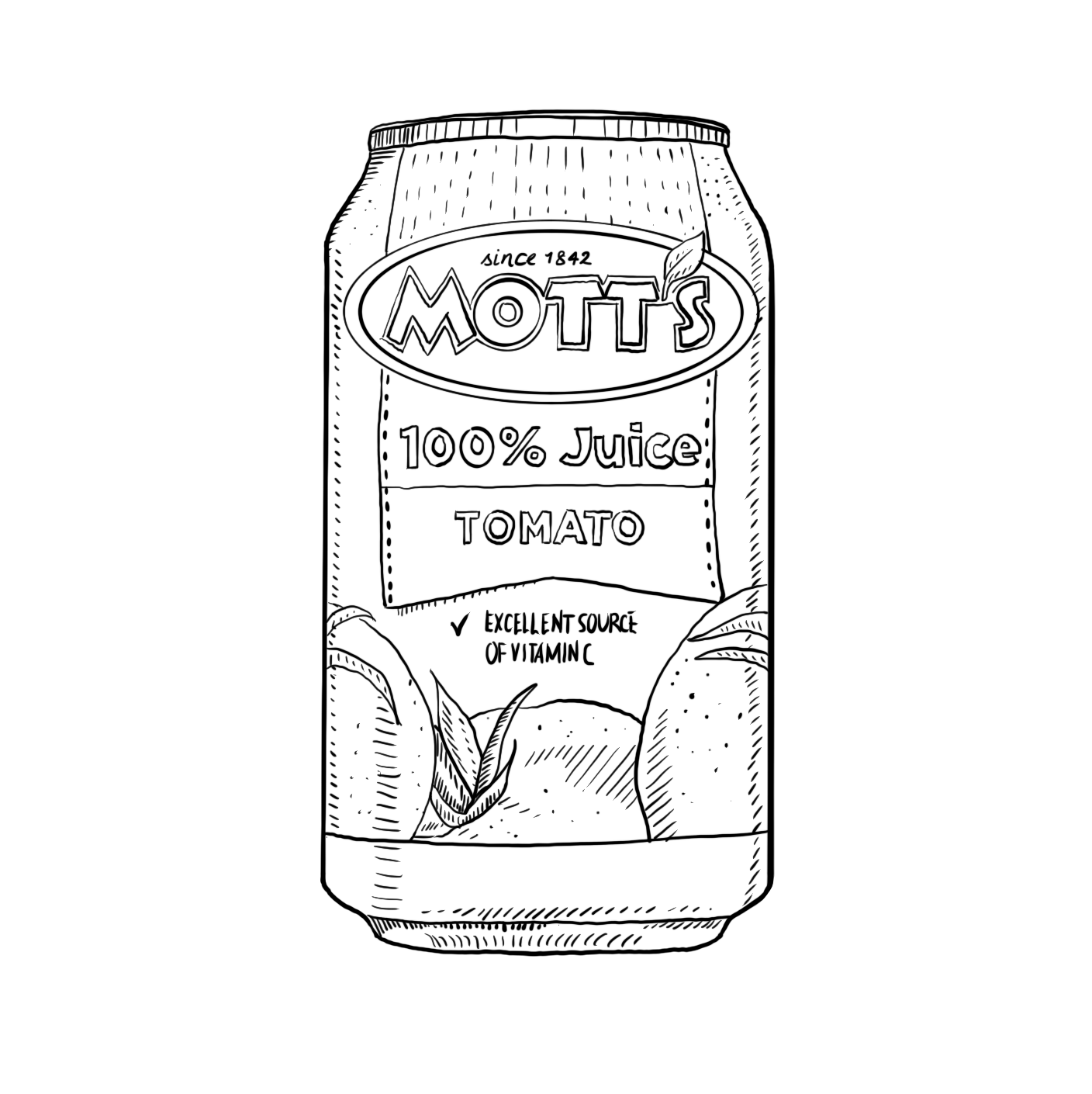

When travelers order a drink in-flight, tomato juice has proven to be a surprisingly popular option. Tomato juice, rich in umami flavor, is perceived as more flavorful and less acidic in the air than on the ground.

Culturally, the tomato juice likely also gained an enduring association with flying from Amelia Earhart’s endorsement and advertisements for Beech-Nut tomato juice in the early days of flying. In a radio interview between 1935 and 1937 when asked what pilots eat while on long flights, famed pilot Amelia Earhart said that tomato juice was her “favorite 'working' beverage--and food too!" [8].

Effects on Passengers

To better understand the widespread aversion to airplane food, numerous studies are being conducted to examine how the environmental factors of the flight cabin might contribute to our sensory experiences of taste and smell.

In 2010, Lufthansa commissioned the Fraunhofer Institute for Building Physics to examine how our perception of particular flavor profiles can change in flight. In the partial fuselage of a decommissioned Airbus A310 placed in a 30 meter long low pressure chamber in Holzkirchen, Germany, researchers had subjects record their enjoyment of different foods at a variety of ambient air pressures. The researchers found that our ability to taste certain flavors is dramatically reduced in flight. Changes in air pressure can reduce the sweet and salty signals to the brain by up to 30 percent, and the dryness in the flight cabin can suppress our sense of smell, an important factor in taste [5].

Changes in noise levels were also found to affect people’s ability to taste flavors. A 2015 study from Cornell researchers found that high decibel sound heightens one's preference for savory foods, especially the umami flavor [6]. Umami-rich ingredients, such as seaweed, mushrooms, tomatoes, and soy sauce helped to provide a better taste and aroma experience. Given that the typical noise volume in an airplane in mid-flight is between 85 and 105 decibels [7], the auditory levels of an in-flight cabin may contribute to our food and beverage preferences.

“Ingredients such as cinnamon, ginger, garlic, chile and curry do not need as much adjustment and maintain the taste of the food… [It is] better to rely on naturally intense flavors, such as orange and tomato oils and tomato concentrate, instead of simply increasing salts and sugars” [4].

What-Ifs

What if airplane meals reframed the relationship between the senses of sound and taste?

Taste tests in simulated aircraft environments have demonstrated that the high noise levels in the cabin decreases our ability to taste flavors. In order to mitigate this impact, British Airways introduced a synesthetic approach combining the sound and taste senses. Based on the research of Charles Spence, a professor specializing in the brain’s integration of information across different sensory modalities, British Airways unveiled the “Sound Bites” initiative on their long haul flights in 2014 [9]. The initiative paired playlists with the offerings of the airline menu so that sound may beneficially, rather than negatively, impact one’s sense of taste.

What if passengers purchased meals at the airport to be eaten on the plane instead of having it catered on the plane?

In-flight catering involves a very complicated system of preparing meals based on flight occupancy and dietary restrictions. There are also concerns of hygiene, quality, recycling, and disposal. If meals were prepackaged and purchased prior to boarding, airlines need only be responsible for waste disposal. An example of this system is implemented on Japan’s bullet trains. Passengers of Japan’s bullet trains purchase lunch boxes to eat on the train called “Ekiben”. Each destination has a different style of lunch box for passengers to enjoy. Waste is kept to a minimum and passengers are responsible for the disposal of their own trash when departing. A similar system could be implemented for short-haul flights.

- Romli, F I, K Abdul Rahman, and F D Ishak. 2016. “In-Flight Food Delivery and Waste Collection Service: The Passengers’ Perspective and Potential Improvement.” IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 152 (October): 012040.

-

Eisenbrand, Jochen. 2004. “Dining Aloft.” In Airworld: Design and Architecture for Air Travel. Vitra Design Museum.

-

Avakian, Talia. 2019. “How Airline Food Is Made, According to the Experts.” Travel + Leisure. July 18, 2019.

-

Gajanan, Mahita. “This Is the Real Reason Why Airplane Food Tastes So Bad.” Time, August 14, 2017.

-

Terseglav, Assja. “Fraunhofer Flight Test Facility.” n.d. Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft. Accessed August 20, 2019.

-

Yan, Kimberly S., and Robin Dando. 2015. “A Crossmodal Role for Audition in Taste Perception.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 41 (3): 590–96.

-

Moskvitch, Katia. “How to Cut Noise in a Plane Cabin.” BBC Future. BBC, February 26, 2014.

-

Martyris, Nina. “Amelia Earhart's Travel Menu Relied On 3 Rules And People's Generosity.” NPR, July 8, 2017.

-

Spence, Charles. “Tasting in the Air: A Review.” International Journal of Gastronomy & Food Science 9 (October 2017): 10–15.